9 Rules for Good CustDev: How and Why to Ask Questions to Potential Customers

Unlock the secrets of effective Customer Development! Discover 9 essential rules to ask better questions and gain valuable insights from potential customers.

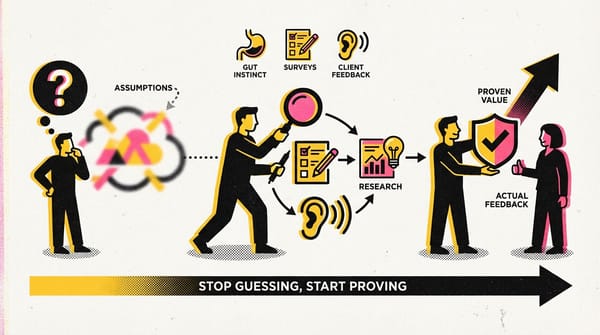

Customer Development (CustDev) is a methodology for creating products or startups based on validating the idea or prototype of the future product through potential consumers. This process involves gaining insights from users to create, validate, and optimize product development ideas through structured interviews and experiments.

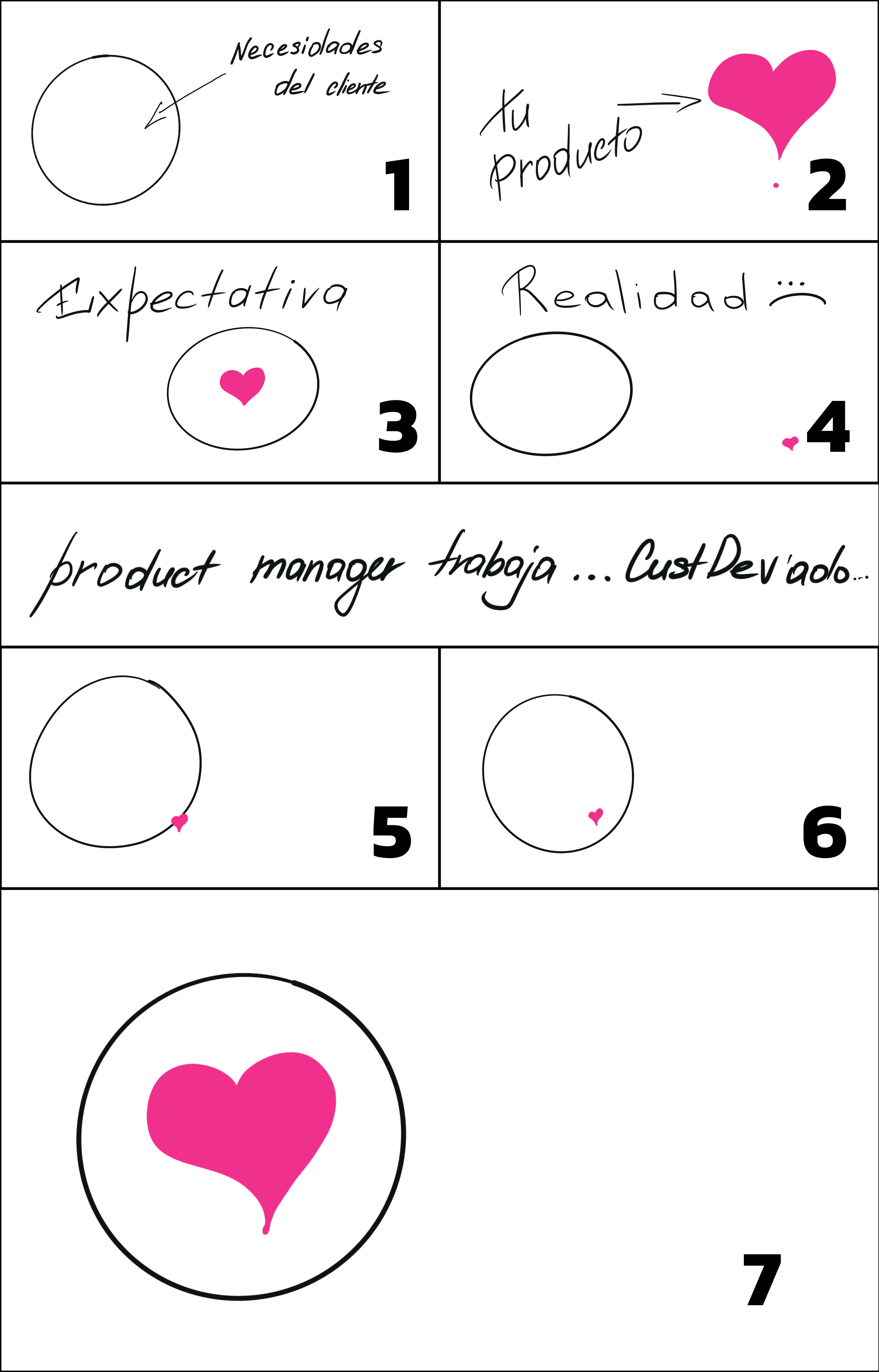

For a customer to want to buy something from you, you must solve a problem or meet a need. The product itself, no matter how great and innovative, will not sell on its own. In essence, this is a customer-oriented approach to business where the product solves the customer's problem. First, the problem is identified, and then the product is developed, not the other way around.

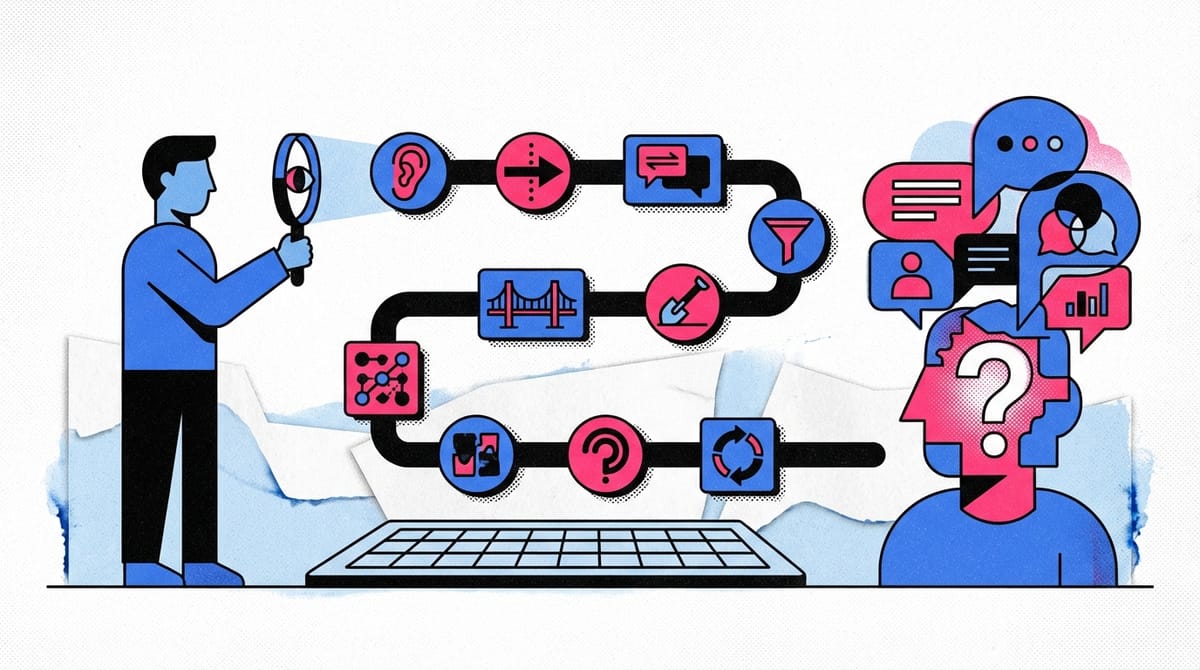

Vanya Zamesin, a product manager at Yandex, drew a picture that explains why product management is needed and its individual parts, including customer development.