Apples, Not Pineapples: Making Vacancy‑First Real with Triple Validation

Discover the power of "vacancy-first" with triple validation! This approach ensures that only the most relevant skills (or "apples") are presented, eliminating distractions (like "pineapples") and streamlining your job application process for success.

A story about apples, pineapples, and the third path

On paper, I had it right from the start: vacancy‑first. Not a resume, not “look how shiny I am,” but a clear answer to the employer’s request. The vacancy asks for apples — we bring apples. Period.

Only the model refused to live in that world. I politely said, “Apples, please.” It smiled back, “How about some wonderful pineapples?” I strengthened phrasing, tuned the prompt, added constraints, removed heuristics. The vacancy kept asking for apples, and the model kept enthusiastically pitching pineapples. Groundhog Day, with a tropical scent.

I pushed. I pleaded. I wrote examples, counter‑examples, and mapping tables. And… nothing. At best, it agreed to offer a pear. It felt like there was a professional exotic‑fruit salesperson living inside, convinced that “the right fruit is the one that looks flashier.”

So I did what people do when logic stops helping: I fed it ten pages of theory on how to respond to job postings. Reply structure, pain points, critical responsibilities, resonant achievements, employer risk factors, domain context. I wanted to believe it would “understand.” It didn’t — not really. But something shifted. As if a weak magnet for the word “apple” appeared inside the model, though still not strong enough to turn the compass needle.

Honestly, I was tired. Instead of another ritual of “one more prompt and it’ll work,” I brought in a different model. Opus. A fresh head from a different school. And on the very first run it didn’t argue about fruit. It proposed a third plan — triple validation. And suddenly the puzzle began to click.

Setup: “apples vs. pineapples”

Mistakes feel pleasant when they’re elegant. Mine was exactly that. I thought “vacancy‑first” meant compiling the right list. In reality, it’s about a discipline of deference. The model kept trying to push its own priorities: louder, brighter, more impressive. I asked for apples; it offered pineapples because pineapples rank higher in a global “skill flashiness” leaderboard. The algorithm worked — just in service of the wrong goal.

Even ten pages of theory didn’t cure the “pineapple reflex.” They only turned the volume down: the model mentioned “apple” a bit more often, but still wheeled out the “juicy exotic” to the front of the display.

Turn: the third way

Opus behaved differently. It didn’t argue about which fruit is “generally better” — it suggested a procedure where a pineapple simply has nowhere to slip through if an apple is required. Not a ban, but a sequence of doors through which only the necessary item can pass.

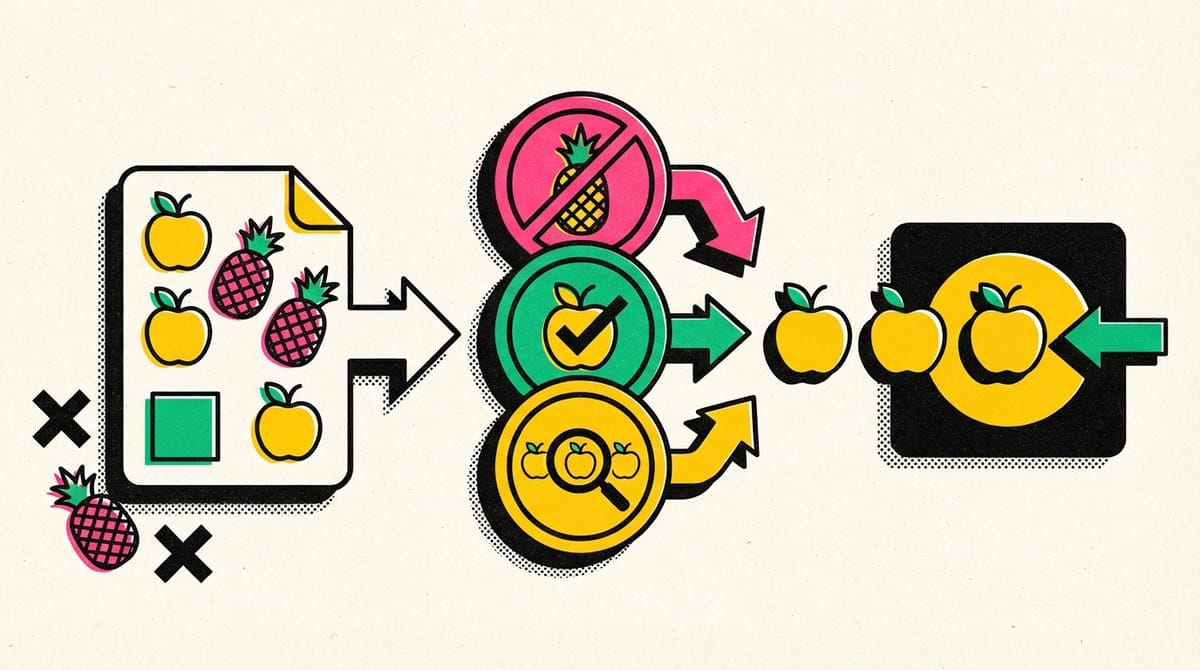

Triple validation looked like this.

1) Vocabulary validation against the vacancy

First, we form a requirements list from the job text. Not a fuzzy synonym cloud, but strict seed terms: responsibility names, key skills, derived word forms. At this stage any “pineapple” gets filtered out because it doesn’t map to the vacancy’s vocabulary. If a term doesn’t appear explicitly or via vetted synonymy, it’s not “today’s fruit.”

2) Evidence validation from the resume

Next, every potential “apple” must show a receipt: where exactly in experience it’s backed up. Not just “I can do budgeting,” but “reduced X by Y, managed Z worth N, implemented process M.” No evidence in experience — the item drops out, no matter how juicy it looks. Even the most aromatic pineapple is powerless here: without evidence it’s just a label.

3) Role‑context validation

Finally, we check for fit by level and environment. If the vacancy is for operations management and the skill is a rare senior‑level strategic fruit, it may be “great,” but it’s out of place. This stage eliminates items that passed the first two doors yet don’t match the tone, scope, or responsibility needed today. It calibrates the final set to the reality of the vacancy rather than an abstract “maximum.”

After that, there’s simply no room in the funnel for exotic items “because they look nice.” If the vacancy wants apples, the result is apples. Maybe with cinnamon. Maybe with a knife and cutting board. But definitely not pineapples.

Action: what changed in the system

I rewired my pipeline to follow this order:

- instead of “pick top skills first and ask the model to figure it out,” it became “list the vacancy’s requirements strictly first”

- then I added an evidence layer: for each requirement — exactly where in experience the proof lives, with a pointer to the fact

- and on top I added a role‑context layer so level or domain mismatches don’t slip through

What’s interesting is that no heroic code changes were needed. Rhythm was what mattered. When the door order is right, prompts get shorter, JSON breaks less often, and the model hallucinates less. Where I used to twist knobs and argue, I now just mark “pass” or “fail.”

Climax: the moment of truth

A test that used to fail started returning a meaningful list. In the same spots where the model had previously pulled in “flashy” skills off‑topic, it calmly admitted: “no evidence,” “wrong for role tone,” “not required by vocabulary.” And the best part — when apples were required, they finally came first. If there weren’t enough apples, the list stayed honestly sparse instead of cheekily swapping them for “pineapples to try.”

That’s when a sense of truth appeared. Not because there were more checkmarks, but because the excuse “well, this is also nice” disappeared. A clean “yes or no” remained. A simple criterion you can stand behind.

Resolution: what triple validation taught me

- Vacancy‑first isn’t about “saying the right words.” It’s about an architecture where pineapples have nowhere to live.

- Theory helps, but on its own it only nudges the compass needle. Procedure sets the course.

- Models respond better not to “one more example,” but to “one more door.”

- The right order of checks cures 80% of prompt magic. The rest is craft.

And perhaps the most important point for anyone just getting acquainted with AI: don’t try to talk a model into accepting apples. Build a process where apples are the only outcome when they’re actually requested. It smiles at words. It obeys procedures.

From that moment I argued less and simplified more. Three doors, then the result. If it doesn’t pass — those aren’t our apples. And that’s an honest answer too.