Why Your Product Marketing Fails Without a Defined Audience

What Product Marketing Actually Means

Let's talk about what product marketing actually means. If we don't get aligned on this now, everything that follows will feel disconnected. This might seem basic, but stick with me — it's the foundation for everything else.

You could define product marketing as a sum of textbook terms: positioning, go-to-market strategy, customer research, messaging. But that's boring and unhelpful. Let me explain it with a deliberately simple example — so simple it makes the underlying logic crystal clear.

From Fruit To Product: The Nectarine Example

I have a nectarine. Right now it's just a fruit — an object, not a product. It's not a product because I haven't offered to sell it to you yet. And if it's not a product, there's no marketing to speak of.

But let's say I decide to become a nectarine mogul and want to sell these wholesale. Now the nectarine becomes a product. I could run ads right now and maybe even sell a few. But if I just start advertising without any strategy, I'm in a pretty dumb position — I don't know what to say, where to say it, who to say it to, or how.

I know nothing about my target audience. Should I show ads to health-conscious snackers? Young parents? Athletes? Restaurants? Corporate catering? School cafeterias? I have no idea.

The first question to answer: who are we selling to? The options are endless — young parents, fitness enthusiasts, pastry chefs, restaurant owners, catering companies, schools, summer camps, grocery stores, and on and on. We need to pick an audience.

Let's say we decide to focus on fitness enthusiasts. Why? Maybe there's a strong fitness community in our area, we understand their mindset, and our founder is one of them — so the company genuinely believes in that culture.

What problems do fitness people have? They want to eat something after a workout, but they can't have junk food. They want more fruit in their diet. They're doing intense training and need fuel that doesn't sabotage their goals. Obviously these people have many other problems in life, but for our purposes, these are the ones we can address.

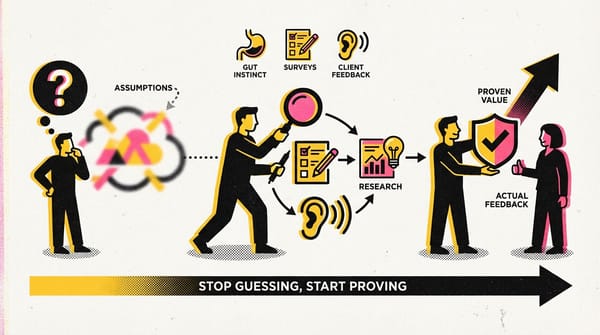

How did we learn this? Maybe we ran some interviews, read through Reddit threads and fitness forums, talked to real people. Plus our founder lives this lifestyle and knows the pain points firsthand. Okay — checkbox: we understand our customer's problems.

Next: the product. The question here is: what form should this product take to best solve our customer's problems?

This nectarine could be sold individually. Or in a multi-pack. Dried. As purée. As a smoothie. As frozen yogurt. As a cake topping. Canned in syrup. The options are nearly infinite.

How do we know which one is right? If we're actually in the nectarine business, it makes sense to talk to people already doing it. But if we're building something new, there's no universal rule. We can only form a hypothesis and test it.

Honestly, about two-thirds of a marketer's job is exactly this — thinking through hypotheses. There's surprisingly little mechanical work. Most of it is thinking: forming hypotheses, testing them, then either generating new ones or scaling the ones that worked.

Let's say we came up with two hypotheses:

1) We sell dried nectarines in resealable pouches.

2) We sell nectarine smoothies.

Good — we've defined our product options.

So here's where we are: We believe our buyer is a fitness enthusiast with specific problems, and we're solving those problems with our product. That's our working hypothesis.

Turning Product Into Story: Messaging

Now we need to tell people about this product. What do we say? That it's "just fruit"? A "healthy snack"? A "guilt-free treat"? A "vitamin boost"? Do we emphasize that it's sweet, or that it's healthy? Or do we try to say everything at once?

This is where you work with a copywriter and designer to craft your messaging. The designer might say, "Let's make the background pink — it matches the fruit." And you say, "Hold on — we're targeting athletes. Let's make it feel more energetic." Or the copywriter drafts something like "An exquisite flavor experience..." and you push back: "We're selling to people who care about macros and recovery. The copy needs to be about energy, vitamins, and performance."

Great — we've figured out our messaging direction.

Acquisition And Economics

Now let's talk about two things that are deeply connected: acquisition and economics.

Say I go to Facebook to advertise my nectarines. Facebook says, "That'll be $50 for this campaign." I pay, I run the ad. 500 people click through, 50 of them buy. That means each customer cost me $1 to acquire.

Now the question: Can I afford to pay $1 per customer? Does that fit my economics? Is that expensive or cheap for my business?

Let's do the math. Say the cost to produce one pouch of dried nectarines is $5. It's a premium product, and I sell it for $10. In my ad campaign, I spent $1 to acquire each sale. So: $5 cost, $10 price, $1 acquisition — I made $4, right?

Not so fast. Once you factor in taxes, shipping, payment processing fees, your own time (or employees' salaries), software subscriptions, and other overhead — you might actually be losing money. The economics didn't work.

What do you do?

- You could raise your price.

- You could tweak the product to reduce costs.

- You could change the package size to shift the unit economics.

- You could find cheaper advertising channels.

- You could increase the average order value — sell a 5-pack instead of a single pouch.

When we start talking about selling five pouches at once, we hit a crucial topic: retention.

Retention is when a customer who bought once comes back to buy again. The second time, you don't pay to acquire them — they just return on their own. If they keep buying over time, even a $1 acquisition cost becomes profitable because their lifetime value far exceeds it.

If someone eventually spends $200 with me, and I only paid $1 to acquire them, I'm doing great. That's the whole point of retention — it's how you turn a marginal first sale into a profitable relationship.

Look at what we just did: we walked through the entire product marketing process for one humble nectarine. We formed hypotheses. Now we test them. If something doesn't work, we iterate.

Let's say we launched both products — dried nectarines and smoothies. The smoothies flopped at that price point, but the dried nectarines? Our fitness crowd got hooked. What now?

We rework the failed product — maybe we put the smoothie in a can so it's easier to drink on the go. And we upgrade the winning product — put the dried nectarines in a sleek metal tin that looks premium and reusable. These are just examples.

After we repackage the product, we start the cycle again:

- Redo the messaging.

- Redo the acquisition strategy.

- Recalculate the economics.

- Rethink the retention system.

And here's the big question: What is marketing, really?

Marketing is all those checkboxes along the journey: understanding your audience, defining their problems, shaping the product, building the economics, choosing channels, and driving retention. That's what a marketer thinks about. Obviously they don't do it alone — researchers help with insights, copywriters with messaging, designers with visuals, finance people with the numbers. But the marketer sits at the center, connecting all of it.

To sum it up: Product marketing is the process of creating something that specific people need, in a form that solves their problems the way they want, at a price they'll pay, through channels they'll find, in a way that makes you money — and keeps them coming back.

That's the whole picture. Ideally, it also scales: if you invest 10x more in ads, you earn 10x more. But scaling is a topic for another time.

We've covered the big picture of product marketing. Now we can get into the specifics.

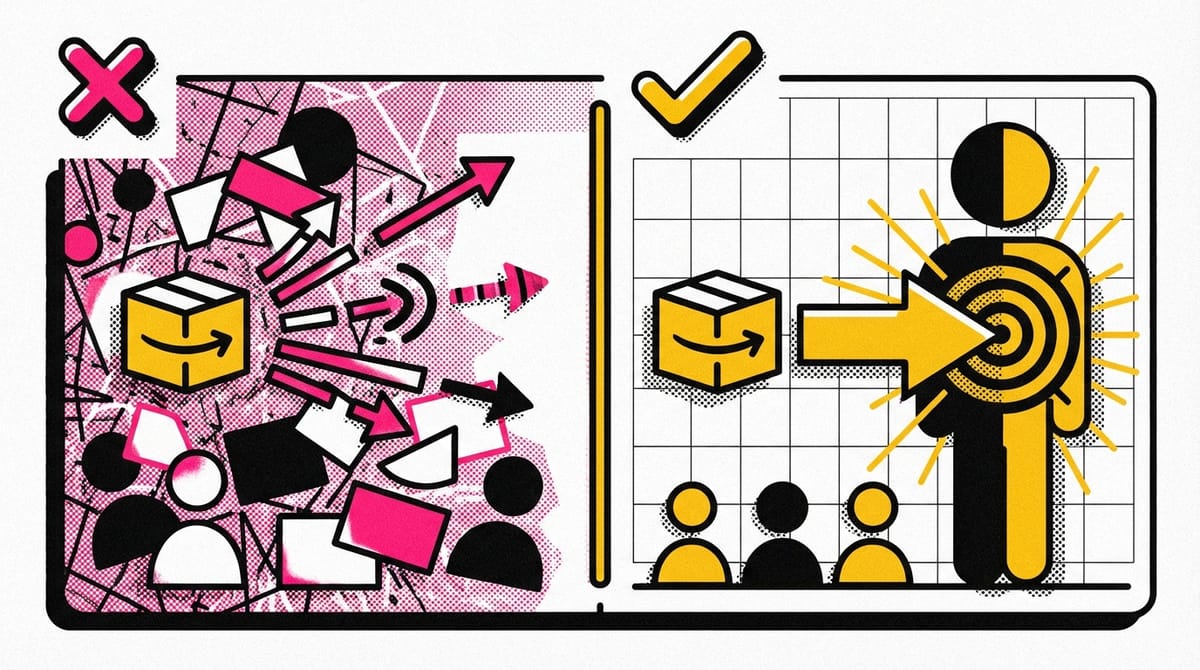

Why Your Marketing Fails When “Everyone” Is Your Audience

You can be brilliant at what you do and still struggle to get clients.

Not because your skills are weak, but because your positioning is fuzzy.

This article is about fixing that, starting from the most basic question most solo professionals skip: who exactly is this for?

Product Marketing For Solo Pros (Without the Jargon)

You will not see funnels, MQLs, or “go-to-market frameworks” here.

Think of product marketing as the system that answers a few brutal questions:

- Who exactly am I helping?

- What problem do they feel every week?

- How does my service show up in their life?

- How do I talk about it so they instantly get it?

- Can I afford to keep acquiring and serving these clients?

If you skip any of these, you end up in the “cheap and replaceable” layer of the market, where clients haggle, churn, and treat you like a pair of hands.

If you get them right, you move into the “premium and reliable” layer, where clients come back, refer you, and pay your real rate.

From “Fruit” To Offer: Why Your Service Isn’t A Product Yet

Imagine you’re holding a nectarine.

Right now it’s just a fruit. Not a product.

You are not offering it to anyone. Nobody can buy it. There is no marketing to do.

Your service is often in the same state.

- “I do product consulting.”

- “I build websites.”

- “I automate stuff with AI.”

- “I help with content.”

That’s a fruit description. It says what it is, not who it is for or why it matters.

The moment you say:

- “I help early-stage SaaS founders stop guessing and actually define who their product is for.”

- “I help solo coaches turn chaotic leads from Instagram into a predictable onboarding pipeline.”

- “I help agencies stop bleeding money on manual work by automating their repetitive processes with AI.”

Now your nectarine turned into a product.

You attached it to a specific person with a specific problem.

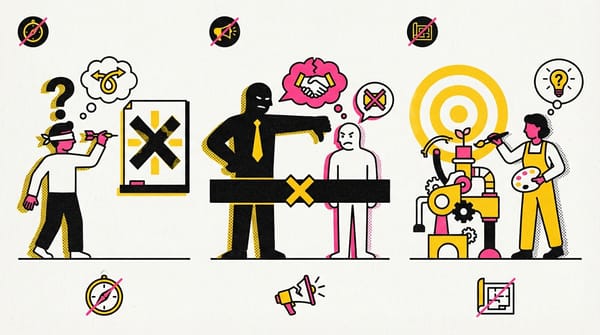

Bad version (anti-example):

“I help businesses grow using modern digital tools.”

Good version:

“I help B2B founders who already get inbound leads but have no system to convert them reliably into paying clients.”

Same skills. Different layer of the market.

Step 1: Choose Your Actual Audience (Not “Anyone Who Pays”)

Most independent professionals secretly sell to “everyone with money.”

You see this in vague positioning:

- “I help small and medium businesses…”

- “I work with startups and enterprises…”

- “I do AI automation for any niche…”

When you’re for everyone, you’re trusted by no one. You become a replaceable line item, easy to push down on price.

Pick an audience you can actually understand and care about:

- A freelance product manager might choose “founders of B2B SaaS between first revenue and $50k MRR.”

- A developer could choose “solo course creators who are drowning in operations.”

- An AI specialist might choose “agencies that already sell done-for-you services, but are stuck on fulfillment.”

- A creator might choose “subject-matter experts who want a weekly newsletter but have no time to write.”

How do you choose?

- You’ve been that person.

- You’ve worked with several of them before.

- You understand their language: what a bad week looks like, what a “good client” means to them, what they are afraid to say out loud.

You are not trapping yourself. You’re choosing a layer of the market where you can be seen as a partner, not a commodity.

Step 2: Map Their Real Problems (Not What You Wish They Had)

Once you pick your audience, you ask:

“What is painfully annoying for these people right now that my skills can reliably fix?”

Example: Freelance product manager working with early SaaS founders.

What they actually deal with:

- Random feature requests from every direction.

- No clear picture of who the product is really for.

- Sales promises one thing, the product does another.

- Founders wake up at 3 a.m. sure the whole thing is about to collapse.

Example: AI automation specialist working with agencies.

Real problems:

- Staff do the same manual crap every week.

- Profit margins are thin.

- Every new client feels like reinventing the wheel.

- The owner is stuck inside operations instead of sales.

Example: Creator / content professional serving consultants.

Real problems:

- Consultants spend 4 hours on a LinkedIn post that brings 3 likes and zero leads.

- Their best ideas live in long voice notes and chaotic docs.

- They hate content, but they need visibility to get good clients.

Notice what these problems have in common:

They create anxiety. Lost time. Lost money. Dented reputation.

Your job is not just to “deliver a project.”

Your job is to reduce that anxiety in a way they can feel.

Bad version (anti-example):

“I help you create content consistently.”

Better version:

“I help you ship one high-quality LinkedIn post every week that speaks to the exact clients you want, without you touching a blank page.”

Step 3: Shape The Offer To Fit Their Life

Now we turn the fruit into a format they can actually use.

A nectarine can be:

- Fresh fruit

- Dried snack

- Smoothie

- Dessert topping

- Juice

- Frozen yogurt

Same base, different forms.

Your skills are the same.

Take “product management,” “development,” “AI automation,” “content,” “strategy” — these are raw fruit.

Format options:

- One-off audit: Deep dive, report, implementation roadmap.

- Project: “In 4 weeks we go from chaos to a simple, working system.”

- Retainer: “You get ongoing product support / content / automation as you grow.”

- Workshop: “Half-day with your team to untangle the mess and make real decisions.”

- Done-with-you sprint: “We work together side by side for 10 days to ship X.”

Anti-example:

“I offer consulting, mentoring, and implementation. Packages available.”

This is a fruit basket.

Better:

“I run a 4-week ‘Positioning Sprint’ for B2B SaaS founders. We define who your product is really for, clean up your messy feature set, and create a simple narrative that your sales deck, website, and product can all agree on.”

Now your offer is:

- Time-bound

- Concrete

- Designed to remove a specific anxiety

That’s a product.

Step 4: Get Ruthless With Your Messaging

Once your offer is shaped, you need to talk about it like a human.

You are not writing for CMOs. You are writing for:

- A founder reading emails at midnight.

- An agency owner between client calls.

- A consultant scrolling LinkedIn while a client is late to a call.

- A developer who hates marketing but needs clients.

Bad messaging (anti-examples):

- “End-to-end solutions for business growth in a dynamic environment.”

- “Leveraging AI to transform your digital ecosystem.”

- “Helping companies of all sizes unlock their potential.”

None of this reduces anxiety. It doesn’t even say what you actually do.

Good messaging:

- “You keep shipping features without a clear idea of who you’re building for. I help you define your real audience so your roadmap, marketing, and sales finally pull in the same direction.”

- “Your agency’s profit leaks through repetitive manual work. I plug those leaks by automating the boring parts with AI so you can take on more clients without burning your team out.”

- “You know your expertise is strong, but your LinkedIn presence doesn’t show it. I turn your calls, notes, and emails into a weekly post that brings you real conversations with the right people.”

You are not trying to sound smart.

You are trying to make one specific person exhale and think, “Finally, someone who gets it.”

Step 5: Understand Your Economics (So You Don’t Resent Clients)

Now we hit the unsexy part that quietly decides whether your business survives: can you afford your own business model?

Say you are an AI automation specialist selling a $2,500 “Operations Sprint” to agencies.

- It takes you 20 hours per project.

- You spend $300 per client on software, tools, and contractors.

- You spend $500 worth of your time and money to acquire that client (ads, platforms, outreach, calls).

- You want at least $100/hour effective rate before tax.

Math:

- 20 hours × $100 = $2,000 (your time)

- $300 tools

- $500 acquisition

That’s $2,800 cost to deliver and acquire one $2,500 project.

You are paying for the privilege of working.

Options:

- Raise the price.

- Shorten the project.

- Standardize it so it only takes 10 hours instead of 20.

- Change your acquisition channel so it costs $150 instead of $500.

- Turn it into a 3-month retainer instead of a one-off.

What you cannot do long term is “hope it works out” while you undercharge and secretly resent every new project.

Premium layer of the market = clients pay you enough that you can care.

Cheap layer = you cut corners because the math forces you to.

You choose where you play by how you structure your economics.

Step 6: Retention — Where The Real Money And Calm Come From

The first sale is expensive.

The second, third, and fifth can be very cheap — if you behave like a partner, not a hired hand.

Examples:

- A freelance product manager who runs a successful 4-week sprint is in a perfect position to offer a 3- or 6-month “product advisory” retainer.

- A developer who builds a custom client portal can offer “care and evolution” monthly: bug fixes, improvements, analytics.

- An AI specialist who automates onboarding for an agency can then automate delivery, reporting, and renewals.

- A creator who set up a newsletter can help with ongoing content, repurposing, and list health.

Bad pattern (anti-example):

- You finish the project.

- You send the final deliverable.

- You disappear.

The client files you under “nice, but replaceable.”

Better pattern:

- You finish the project.

- You show the client what problems you have removed:

- You propose a clear next step that protects and builds on that win.

Retention is not “being pushy.”

Retention is protecting the outcome you created together.

This is where the economics flip:

- If a client works with you once for $2,500 and never returns, your acquisition cost might eat half your profit.

- If the same client works with you for a year and spends $15,000, that initial acquisition cost becomes almost irrelevant.

That’s the difference between fragile freelancing and a calm, sustainable practice.

Step 7: Put It All Together As A System (Not A One-Off Trick)

Look at the full journey from the lens of a solo professional:

- Choose your layer of the market.

- Define your audience tightly.

- Map their recurring problems.

- Shape your offer around those problems.

- Write human-first messaging.

- Check your economics honestly.

- Design for retention.

Once you see your work this way, you stop acting like a desperate applicant sending proposals. You start acting like what you really want to be: a partner who understands the client’s business and helps it stay alive.

Your Next Move

Pick one current or recent client. Do this on paper:

- Write down who they really are (not “industry,” but role, stage, situation).

- List 3 problems they had before working with you that showed up every week.

- Describe your actual offer to them in one sentence, as if you were explaining it to another founder.

- Estimate, honestly, how the economics looked for you.

- Write one concrete way you could continue helping them for the next 3 months without creating fake work.

You have just done more real product marketing than many “growth teams.”

Do this for a few clients, and patterns will start emerging.

That’s your audience.

That’s your positioning.

That’s your path into the premium, reliable layer of the market — where clients keep coming back not because your portfolio is shiny, but because life is simply better with you on their side.